ATTENTION ECONOMY

How I learned to stop worrying and love the amphetamine shortage

There is, as of September, a shortage of Adderall in New York City. While the city’s amphetamine supply is always in some state of flux, this one was predictable: right as school started back up and every college student needed their script refilled, right as every investment banker returning from the Hamptons realized they couldn’t face Q4 without pharmaceutical assistance. This isn’t a “some pharmacies are out” shortage, but a legitimate, citywide, panic-inducing shortage where people are calling fifteen different CVS locations, reading Reddit threads where strangers crowdsource which outer-borough pharmacy might still have a supply, texting psychiatrists and drug dealers with the urgency once reserved for actual emergencies, rationing their pills like we’re in some kind of productivity dystopia, which, I guess, we are.

I know about the shortage not because I’m affected directly (more on that in a moment), but because I work in a small office in Williamsburg (I don’t technically work there, I just show up several days a week to a place where people who have actual jobs tolerate my presence because of my good humour and charm, or maybe I just say that to make myself feel better about the fact that I don’t have a real job). And in this office, on a recent Tuesday afternoon that was distinguished from other Tuesday afternoons only by the quality of cooler air coming through the window and the particular blend of drip coffee I was drinking (from the deli, lukewarm, black, which I mention not because it matters but because these kinds of granular details are how we differentiate one identical day from another), Arni announced that he’d stopped taking his Adderall. The energy in the room shifted. Three other people (all of whom I now understand to be regular Adderall users) turned toward him like plants to light.

“So you have extras,” someone said. Not a question, but observation.

“Two bottles,” Arni confirmed.

What followed was a negotiation with the intensity of a drug deal, except it was happening in a bright, quirkily decorated office with an espresso machine and an underwatered Monstera. The kind of scene that would have been strange thirty years ago—or rather, typical, but in a different setting, involving different people, carrying different moral weight. Now it was just Tuesday. Three professionals with health insurance converging on a surplus of amphetamines with the urgency of people who cannot do their jobs without them.

I sat there, drinking my deli drip coffee, thinking about my own ADHD diagnosis, which I received a little over a year ago after spending $1500 on what was called a “comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation,” though it was neither comprehensive nor particularly neuropsychological. It is the kind of exam where you go on a thirty minute Zoom call and some psychiatric nurse practitioner asks you six questions that you give kind-of true answers to, about whether you “often,” “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” lose your keys (I said “never,” as my City Bag is an extension of my own body). Whether you had trouble paying attention in school (“rarely,” though that was mostly because I never did the readings so instead I dutifully went to every lecture and clung to the professor’s every word). Whether you interrupt people (“sometimes,” but is that pathology or just conversational impatience?)

At the end, the nurse tallied my results and said, “Yes, you have ADHD, predominantly inattentive type.” I remember feeling both triumphant and suspicious. Triumphant because: a justification for why I can read Knausgaard for six hours but cannot respond to an email, why I can remember every Prince album in order by year but forget to pay my credit card bill for twelve days. Suspicious because: isn’t that just being a person now? Doesn’t everyone feel like this?

The psychiatrist I was referred to—a gay guy in his late thirties who had that particular Manhattanite energy of someone who’s been routinely prescribing controlled substances to high-functioning neurotics and has developed a very efficient system for processing them—told me during our thirty minute telehealth appointment that yes, 10mg Adderall XR seemed reasonable, that no I shouldn’t take it every morning, just on days when I needed to focus, and that before he could send the prescription I’d need to get a physical exam to make sure the amphetamines wouldn’t make my heart explode or whatever cardiovascular catastrophe he was legally obligated to screen for.

Reasonable. I made the appointment, I went to the clinic, I let them take my blood pressure and listen to my heart and draw blood and run whatever tests are supposed to reveal whether you’re the kind of person who can handle regular stimulant use. I got the results. Everything was normal. My heart was fine. My cardiovascular system was ready for amphetamines.

I emailed him the results. Nothing. I called the office. Voicemail. I called again the next day. Voicemail. I downloaded their patient portal, one of those medical customer service apps that’s supposed to make communication “easier” but really just adds another layer of digital bureaucracy between you and the human you’re trying to reach. I messaged through the app. The bot that pretends to be a secretary told me someone would respond within 24-48 hours. No one did.

I did this every day for a month. Email, call, message. I tried different times of day in case there was some secret window when someone would actually answer. I tried being polite, then slightly urgent, then borderline desperate, calibrating my tone like I was negotiating with a hostage taker. Nothing. The prescription never came.

Around week four of this Kafkaesque loop, I gave up. Not because I stopped wanting the Adderall, but because the amount of executive function required to pursue the Adderall was itself evidence that I probably didn’t need it that badly. If I could summon the sustained attention necessary to hound a psychiatrist into prescribing me attention medication, then maybe my attention wasn’t that impaired after all. Or maybe the whole thing was just cosmically absurd. Either way, I let it go.

And now, there I was, sitting in the office when Arni made his announcement, when the room shifted, and I shifted with it. I asked if I could have some. He nodded toward his backpack. “Front pocket.” I took out two pills. Put one in my mouth immediately, with some Strawberry-Peach LaCroix, and pocketed the other for tomorrow, or the next day, or whenever. Which is to say: I took Arni’s Adderall to write this essay. I’m on it right now, as I type this.

And although I don’t think I need Adderall to function, I can’t ignore that I simply get so much more done when I’m on it. But doesn’t everyone? Isn’t that the point? The problem is that I don’t know the difference between need and want in this context—and I have a suspicion that most people don’t either. Everyone cloaks this wanting under the very justifiable, clinical word “need.”

But this isn’t really about Adderall. It’s about attention and the world we’ve built that keeps splintering it, then wonders why we need chemicals to cope.

It’s not just the amphetamines, but about the entire apparatus of focus-management: Opal, The Brick, Pomodoro timers, bullet journals, dopamine fasts. An entire cottage industry devoted to enforcing what is supposed to occur naturally. The idea that we need techniques for basic mental presence is itself diagnostic. The fact that we need an entire industry of attention-management systems is evidence that something has fundamentally broken down. And we all know this. We are all constantly talking about the effects of “the phone.” We wouldn’t need elaborate infrastructure to force ourselves to focus if we weren’t trained to crave constant stimulation. We wouldn’t need to brick our phones and block our apps and do Pomodoro sessions if we hadn’t become addicted to the feeling of being engaged, right?

The irony is that none of these systems produce the kind of attention that actually matters. They produce compliance. They let you override your brain’s correct judgement that certain tasks are tedious. You’re not absorbed, but managed. You’re not present, you’re constructing presence.

I have been reading Simone Weil lately, and thinking that what these focus drugs and apps and techniques cannot give you (what they might actually prevent) is the kind of attention that Weil was talking about when she said “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” The kind of attention that requires self-emptying, that means forgetting yourself completely in the presence of something worthy of notice. The kind of attention where you’re not monitoring yourself, not tracking your progress, not optimizing your focus, or performing concentration for an imagined audience. The kind of attention where you just are. A purer kind of presence, lost in something larger than yourself.

You cannot systematize your way into that kind of attention. You cannot download it or pay $59 for a device that enforces it. In fact, the more you try to cultivate it deliberately, the more you use tools and techniques and protocols to manage your attention, the further you get from it. Because now you’re not just attending, you’re also monitoring your attending. Checking whether the system is working, evaluating whether you’re doing it right or if you’ve been doing it for long enough. You’re in a loop of self-consciousness that is itself the opposite of the full, generous attention you’re trying to achieve.

And this is where we start to see the deeper problem. It’s not just that we’re distracted, or that we need Adderall and Opal and Pomodoro timers to focus. It’s that we’re losing the ability to give attention in the way that matters: that is, freely, generously, unselfconsciously. We’ve trained ourselves into a mode of relating to our own consciousness where we’re always managing it, always monitoring it, always optimizing it. We’ve turned attention into a resource to be managed rather than a gift to be given. And if attention is generosity, then the attention I give on a drug that hijacks my dopamine system isn’t generosity per se, but more like pharmacological obedience.

“Locking in” has become the mot du jour, a phrase we use to aestheticize our own self-management. People announce they’re locking in the way they once said they were logging off, a performative gesture toward control—half affirmation, half declaration. It’s funny, really: the very act of saying it implies that attention no longer arrives on its own, that we have to conjure it into being by naming it out loud.

I’m writing this on Arni’s Adderall, and it’s working. I can feel it working. I can feel myself locking in, the focus narrowing, the distractions receding, the ability to sit still and push through the tedious parts of writing. I still check Xwitter once every fifteen minutes but I don’t spend more than a few moments scrolling before I get back to my Task At Hand. The Adderall makes me productive, it makes me capable of sustained attention to a task that requires it.

But what Weil meant when she wrote that “attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity” is that attention is not something that has to do with productivity or the ability to sit through a meeting without checking your phone. She meant a quality of consciousness where the self temporarily disappears. Where you’re so absorbed in attending to something outside yourself that you forget you’re someone who’s attending. You’re not monitoring your attention, not performing it, not aware of it. The boundaries between you and the thing you’re attending to dissolve. It’s when you’re emptied out and the world fills you.

This is the kind of attention that lets you really see something, that lets you notice the particular way afternoon light hits a landscape, that lets you read a book and lose track of time. It requires that you stop thinking about yourself—stop narrating yourself, stop checking whether you’re doing it right, stop wondering how it looks to other people, stop wondering how this moment will appear when you describe it later. It requires a suspension of self-consciousness.

I thought about this recently while watching a father teach his daughter how to tie her shoes.

I was at a coffee shop (that place in Bushwick where the coffee costs seven dollars and comes on a little tray in a handmade ceramic cup that’s slightly too small to justify the price but feels nice to hold, as a way of making the ritual feel meaningful even when it’s mundane). I was sitting by the window, ostensibly reading, when I noticed them outside: the dad with patient hands, the kid maybe five years old, concentrating with that intense focus that children have when they’re learning something physical, something that requires their whole body to cooperate.

And here’s what happened in my consciousness, in order:

I see this and something in me softens. The scene is beautiful, genuinely beautiful in a way that’s almost embarrassing to notice because it’s so obviously sentimental. But it is beautiful, the patience and the concentration and the light coming through the window at just the right angle.

And then immediately, I’m aware that I’m seeing something beautiful, which means I’m no longer just seeing it. I’m seeing myself seeing it. And I’m narrating it: “this is beautiful.” I’m already processing the experience as an experience worth noting. Then I think: should I take a photo? This would make a good photo. The light is perfect, the composition is readymade, the dad’s hands and the child’s tiny fingers working on the shoelaces. Then I think: no, that would be intrusive. They’re having a private moment. I would be commodifying their intimacy, turning it into content. Then I feel virtuous for not taking the photo. I feel like I’ve made the moral choice, the respectful choice. I’m a good person who doesn’t turn genuine human moments into content. Then I wonder if I’m being too self-conscious about this. Maybe taking a photo would be fine? Maybe I’m overthinking it? Maybe the real problem is that I’m so aware of performing ethics that I can’t just be in the moment?

Then I start composing the essay in my head. About the scene and the shoe-tying and what it means about attention and presence and the way we’ve lost the ability to just witness things without immediately processing them as content or stories we will later recount. I start thinking about Simone Weil and generous attention and how this moment, this very moment I’m experiencing right now, is the perfect illustration of how contemporary consciousness prevents that kind of attention.

Then I feel sad about this. About my inability to just be somewhere without narrating it to myself. About the way every experience immediately becomes material, becomes content-in-waiting.

Then I try to “come back to the present.” I deliberately redirect my attention to the father and child, try to see them again with fresh eyes, try to recapture that initial moment of softening. But now I’m trying to be present, which means I’m not present. I’m performing presence. I’m monitoring whether I’m doing presence correctly. I’m in a loop of self-consciousness that has completely destroyed the original moment of genuine attention, like when you become aware of your own breathing and can’t go back to your body’s natural rhythm.

Then I pull out my phone and write a note: “father, tying shoes, photo impulse. something about attention here?” Because if I don’t write it down I’ll forget it, and if I forget it then the moment will be wasted, and at least if I capture it I can use it later, I can turn it into something, even if that turning-into-something is precisely the problem I’m trying to write about.

By the time I look up, they’re gone. They’ve packed up their things and left. I missed the ending of the moment because I was trying to figure out how to be present for it.

This is what I mean by split attention, the contemporary mode. You’re always experiencing yourself experiencing. You’re always narrating the moment while it’s still happening. You’re always in two places at once: in the event and in the future telling of the event. And this split, this inability to be fully present because you’re too busy documenting presence, is not necessarily a personal failure. It’s not that I’m uniquely bad at this. It’s that this is what consciousness is now, the structural condition.

The father and the child were in Weil’s attention. They were absorbed in the task, present for each other, unselfconscious. I was in whatever the opposite of that is, some kind of meta-attention, recursive attention, attention that’s aware of itself attending and therefore can never fully attend. And the worst part is that I know this is happening while it’s happening, which doesn’t help. It actually makes it worse, because now I’m aware that I’m aware that I’m narrating my awareness, and the whole thing becomes an infinite regress that leads nowhere except to a note in my phone and a vague sense of having failed at something I can’t quite name.

The phone in my pocket, the ambient awareness that everything could be content, that every moment might be the moment you need to capture or you’ll lose it—this has changed the structure of experience itself. We don’t just have experiences anymore. We have experiences that we’re simultaneously experiencing and documenting and evaluating for their documentary value. We’re always already in the future, which means we’re rarely actually here.

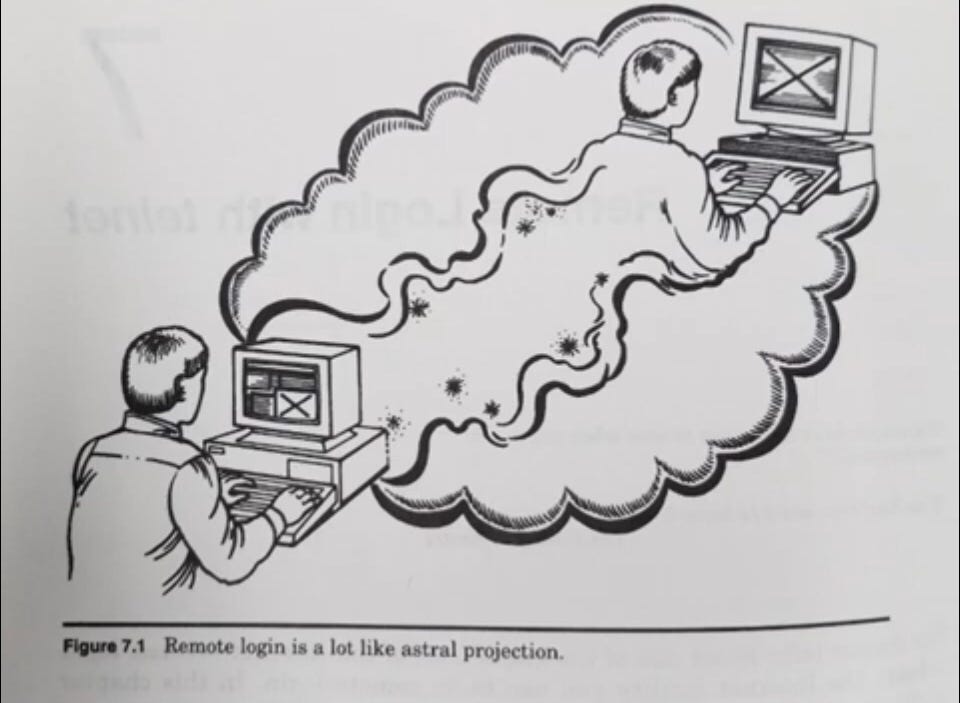

Amphetamines can’t fix that either. It can make you productive, but not present. It sharpens vigilance instead of softening it. You don’t lose yourself—you double yourself. One self executing the task, another monitoring your own efficiency at it.

I’ve noticed that the kind of attention Weil writes about still occurs, but by accident. It happens when no one’s asking for it. It happened this morning, as I was washing dishes, hands in warm water, thinking freely about whatever crossed my mind. It happened last night, smoking outside the wine bar, caught in conversation. It happens in moments where no one is demanding output or self-reflection. Where there’s no reward or imperative of performance. You just happen to be there and the world holds you.

But I lose myself in the phone, too. I scroll for hours, completely consumed—the same narrowing, the same vanishing of self. But the quality of that disappearance is different. The phone collapses attention inward; the world recedes until there’s only stimulus. The dishes, by contrast, open something up. The same self-forgetting, but with space instead of compression. The phone leaves me depleted; the dishes leave me calm. The bar leaves me human.

Maybe that’s the difference between absorption and attention. The first contracts; the second expands. One erases the self while the other empties it.

We’ve trained our minds to expect that attention should feel good. Every micro-interaction (notification, post, like, etc) rewards us instantly. So when you’re asked to do something that doesn’t give you pleasure, your brain rebels. Not because it’s broken, but because it’s been trained to expect that attention equals reward, and now you’re asking it to attend to something boring, something tedious, something that offers no dopamine hit whatsoever. And your brain, reasonably, says: no. Why would I do that?

And yet, the work that matters (thinking, reading, creating, devoting) depends on precisely that unrewarded kind of attention. The kind that doesn’t promise pleasure, that asks you to linger without immediate payoff.

We’ve built a world that constantly confuses stimulation for meaning. We eat synthetic sweetness until fruit feels boring. We scroll through engineered intimacy and forget the ambient fullness of real presence. The same pattern applies to attention: a diet of hyper-stimulation makes the natural forms (reading, walking, noticing) taste bland by comparison. And so we toggle between the two extremes: amphetamine and algorithm, forced focus and frictionless distraction. Both feel like control, but they both hollow us out in different ways. The first commandeers attention while the second dissolves it.

Maybe the disorder isn’t in us, but in the environment that fuels constant, unnatural forms of attending. The culture that requires vigilance and rewards exhaustion. The one that wants us maximally productive and maximally stimulated, and punishes the stillness in between.

When I look back, I realize my so-called “inattention” is rarely random. I can focus on things that are beautiful, urgent, or alive. What I can’t focus on are the dead zones of obligation: emails, forms, logistical detritus. The entire category of things that must be done but mean nothing, tasks without soul. But the attention that feels meaningful is still possible. It just happens less often, and only in the spaces we haven’t yet optimized out of existence.

It happened to me this morning, washing dishes. And last night, in conversation. The week before, walking across the bridge and looking at the skyline with no intention of recording it. Each time, it arrives without being summoned, like the world simply presses through the noise.

Maybe that’s what Weil meant. That attention isn’t something you can practice your way into—it’s something that descends when you’ve stopped managing yourself entirely. It’s grace, not effort. And perhaps that’s why it feels increasingly rare now. Because our lives are structured around deliberate control: self-tracking, productivity, optimization. Even mindfulness is now another system of management. We’ve turned consciousness itself into a project.

I can’t do Weil’s attention right now because I’m on Arni’s Adderall. I haven’t eaten and I’ve had 2 cups of coffee. I have 13 tabs open. I’m focused, but I’m not generous. I’m executing the thought rather than living it. I can describe the condition, but I can’t escape it.

Even so, description feels like a kind of honesty, a record from inside the broken machine. The acknowledgement that the attention I give right now is forced doesn’t make it false, just incomplete.

The generous attention will come again, not because I’ve earned it, but because something, some moment, some object, some flicker of nothingness, will call me back out of myself. And when it does, it won’t feel like focus. It’ll feel like forgetting.

I don't have great attention but it's okay. I used to work with a woman who would just kind of naturally descend into tasks, fully. She did this without drugs. If I wanted to talk to her I had to say her name pointedly, maybe give a little wave. It made me so envious. In a room, my mind is always listening a bit to the room. My peripheral vision is never entirely ignored. I suppose this would be good in an emergency but it's great to lock in. I know that my locking in is a very poor replica of what locking in really looks like.

My mom can do that true lock in, too. I wish she had passed it on to me, but she didn't.

The worst thing, though, the worst thing is when you do find that real flow state. You're totally in the groove. Then you notice that you're in the groove and that is what makes you lose the flow state.

It's like when you're falling asleep and you notice you're falling asleep and that wakes you up.